The Hidden Deficit Holding Back Bike Infrastructure Investment? Data.

For decades, vehicle-centered metrics have dominated transportation planning. But that’s changing. There’s increased public interest in biking, and federal dollars are available for new pedestrian and bicycle projects. Planners need to broaden their lens to keep up.

“It’s kind of scary actually, how little we know about our communities, when it comes to walking and biking transportation,” said Bill Nesper, executive director of the League of American Bicyclists, speaking at StreetLight’s Bike Infrastructure Roundtable.

That lack of data is a function of a historical prioritization of driving measurement. And without information on active transportation activity, it’s extremely challenging to know where to invest in infrastructure that can promote safe and more widespread riding.

But that lack of measurement is beginning to change and it will have an outsized impact on the capacity to make better and safer active transportation investments.

Nesper, alongside Bike Infrastructure Roundtable panelists Jackie DeWolfe of massDOT, Amanda Leahy of Kittelson & Associates, and Jeff Peel of StreetLight, focused on challenges in assessing bike and pedestrian traffic — and how those challenges are starting to be overcome. Below, we discuss how participants on the panel see the active transportation information landscape shifting, and how better measurement can help push biking and walking infrastructure forward.

The fundamental challenge is data availability. While the situation is steadily improving, most jurisdictions work with scant information on bicycling and walking activity.

With thin sources from which to draw out metrics and insights, it’s difficult to prioritize new or improved bike networks, not to mention substantiate an expected return on investment.

And, data that is available typically comes from temporary counters along select existing bike paths and trails, or surveys. These are often scant, and difficult to use to extrapolate a complete picture of biking activity across a region, let alone compare to historical activity.

They are also of limited usefulness when it comes to calculating the potential of new facilities or metrics dependent on context, like climate benefits, or understanding bike projects’ equity profiles.

The problem boils down to “data parity,” or the lack of it. Bike, pedestrian, and other alternative transportation modes are up against the stark fact of a planning landscape dominated by the data cars and trucks throw off.

“For vehicles we have thousands of counters, connected vehicles, and location-based data that provide robust information,” said Jackie DeWolfe, director of sustainable mobility at the Massachusetts Department of Transportation or MassDOT. “And we need the equivalent of that for all modes. Luckily, there’s a lot happening, and there’s future promise for big data to provide that.”

Billions for bike infrastructure up for grabs in five-year push

The stakes are especially high given the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law or BIL, passed in 2021, which earmarks billions for transport improvements. That includes the Safe Streets and Roads for All program, which will award $5 billion annually to states and cities over five years. The grants aim to limit roadways deaths and injuries, including by creating accessible “bikeway networks” and safe bike routes to schools.

Other bike- and pedestrian-relevant funding programs include grants for carbon-reducing efforts and a program known as Reconnecting Communities. The latter program is described by Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg as “the first-ever dedicated federal initiative to unify neighborhoods living with the impacts of past infrastructure choices that divided them.”

League of American Bicyclists won inclusion of BIL spending towards data to support connected network projects.

To firm up grant applications, planners will want to include data and evidence that supports their view of the expected benefit. — Amanda Leahy, associate planner at Kittelson & Associates.

For the BIL programs and other federal and state initiatives, funders want to see quantitatively rigorous analyses to complement qualitative narratives.

Leahy, along with the other panelists, shared examples from Kittelson’s own experience to show how projects can target not only immediate impacts such as changes in travel habits or time- and cost-savings, but also other effects as studies draw on broader qualitative or demographic data sets. These include changes in safety and crash indices, climate impact, and supporting equitable transportation options.

Leahy cited a project that used data to demonstrate measurable health benefits and healthcare cost savings from active transportation investments. Being able to show this kind of ROI is critical to getting community buy-in on active transportation investment, as well as grant funding.

Later she mentioned bike infrastructure’s impact on neighborhood housing costs as another significant metric to weigh.

Measurement sources are tremendously useful here as they offer regular “access to information on how people are traveling, and this helps overcome limitations with more lagging data or less comprehensive data,” said Leahy.

Several panelists commented on the incomplete and outdated data contained in state or national surveys widely used by transportation planners, including the Federal Highway Administration’s National Household Travel Survey.

Most obviously, pre-2020 data does not cover the emergence of Covid-19 and ensuing changes. The pandemic suppressed commuting behavior, led to a boom in biking and walking, and shifted peak travel times. Some of those changes — like the increased adoption of biking — have persisted.

Beyond years-old surveys, the most advanced transportation agencies rely heavily on permanent counters deployed along principal bike paths. They then attempt to infer broader trends from the metrics tabulated from those few counters.

“While those counters get great results, they are limited to the locations and types of travel they are capturing,” said Jeff Peel, a customer success account executive at StreetLight and former deputy director transit at NYCDOT.

In fact, because these counters are sometimes placed in highly trafficked areas, they can support circular logic and planning biases.

Jackie DeWolfe, of MassDOT, mentioned how the preexistence of bicycling and pedestrian activity is sometimes cited as a reason not to place biking and walking infrastructure such as a bike lane or safety crossings on those corridors (the thinking is that there’s no need for additional investment in infrastructure if the behavior is already present).

Instead, DeWolfe said, planners should simply be on the lookout for areas where they can have the most impact.

“That’s why we are actually prioritizing infrastructure based on the potential for biking and walking, not based on counts,” she said.

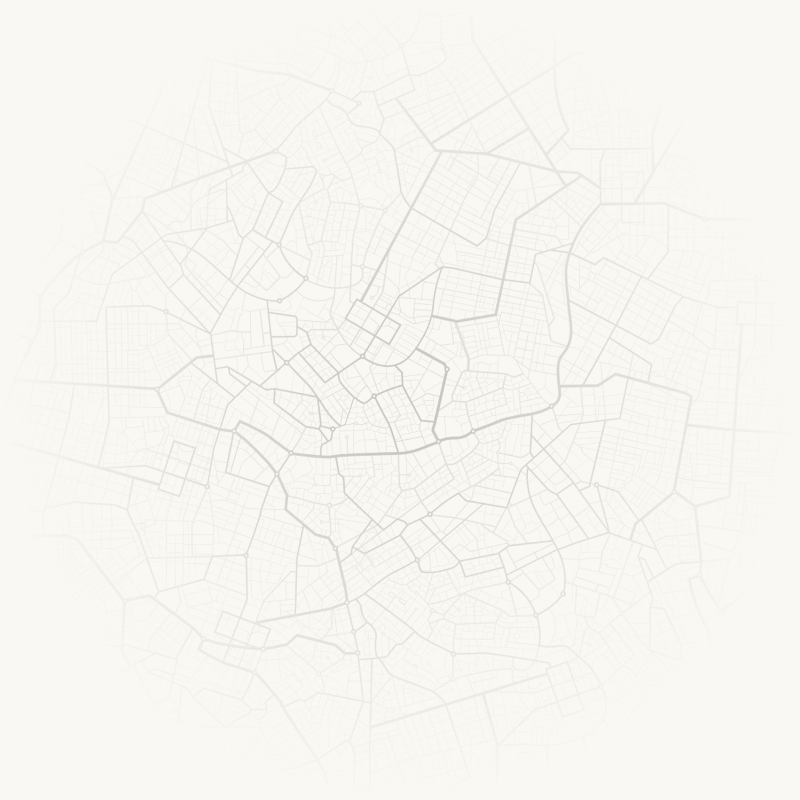

Map of high to low potential biking activity in Massachusetts.

A broader lens on transportation thanks to better analytics

To study walking and biking potential, MassDOT planners have to take in a broader view of study areas to help them understand the relationship between different neighborhoods and how bikers and walkers move through them.

That is why StreetLight has been crucial in this effort. StreetLight ingests, indexes, and processes vast amounts of data from connected devices and the Internet of Things, then adds context from numerous other sources like parcel data and digital road network data – to develop a view into North America’s vast network of roads, bike lanes and sidewalks.

According to DeWolfe, complementing traditional sources with big data-enabled metrics like StreetLight’s has allowed them to improve their insights dramatically, along three important axes:

- Equity: They are able to evaluate equity factors more comprehensively, since they are able to understand behavior across the state without making coverage tradeoffs and compare a large number of locales for considerations tied to demographics.

- Location: Relatedly, they are able to encompass far more locations, since data collection is not reliant on fixed points of collection, e.g. counters that only measure segments of a journey.

- Parity: As mentioned, planners are usually working with a dearth of multimodal data when compared to what is available on vehicle traffic. The big data sources allow them to consider modes like walking and biking on a more even playing field compared to vehicles, which otherwise dominate data sets.

To illustrate the advantages of a broader data palette, the planners shared examples and case studies.

DeWolfe gave an example from the pandemic’s early days. Having StreetLight, MassDOT planners were able to follow along almost in real time as traffic patterns quickly changed. They immediately saw how walking and biking activity shot up. Unfortunately, so did car speeds. Data showed a “horrible” deterioration in safety.

Planners responded with more than $30M in spending for safety fixes for scores of corridors across the state.

“This was just huge,” said DeWolfe. “Otherwise everything would have been focused on vehicle miles traveled. We were able to complement it with walking and biking activity and tell a different story.”

Importantly, DeWolfe pointed out that counters — temporary or permanent — are a part of the portfolio of data sources used by MassDOT, which includes field surveys and other methods as well. In fact, counters are useful in cross-checking and calibrating big data sources. In other words, the solutions aren’t mutually exclusive. Rather, they are most effective when joined together.

What do planners want to see more of as they build a larger ecosystem of active transportation infrastructure?

They cited a need for better integration of safety and crash-risk data, deeper qualitative studies on trip purposes, and more granular insight into demographic and equity trends.

Equity, in fact, is a thread that runs through the BIL and other relevant state and federal programs (although it tends to be defined differently in each instance). It’s expected to be a recurring topic for planners, driving demand for robust demographic and trip-analysis data.

As transportation agencies and Architectural, Engineering, & Construction agencies (AECs) get to work applying for and deploying BIL funds, data will be central to making a case for active transportation investment, measuring how conditions are changing in real-time to see impact, and assessing the demographics of beneficiaries to ensure equitable outcomes.