Transit Equity for Essential Trips: Lessons From Richmond

Transit Equity for Essential Trips: Lessons From Richmond

We’ve learned a lot about America’s more than 50 million essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, but we still know very little about their travel needs. This gap is critical to bridge if we are to help these employees get to work and support rebuilding our faltering economy.

In many cities, transit availability is greatly reduced because of lockdown restrictions, social distancing requirements, and growing budget issues. But limiting transit access poses serious equity concerns for access to work, medical services, and other important amenities.

How can cities optimize mobility — via transit and other options — for essential workers? We turned to Big Data to learn more.

Which Communities Don’t Have Access to Cars?

We know essential workers are often socially or economically disadvantaged. A recent study found essential workers, on average, make less than non-essential workers. With a median hourly wage of just $13.12, essential workers in the food and agriculture industry earn the least. Nearly 70% of essential workers do not have a college degree.

We wanted to learn more about how transit systems serve disadvantaged residents, and we decided to analyze Richmond, Virginia during the state’s first lockdown from April 1st to May 31st.

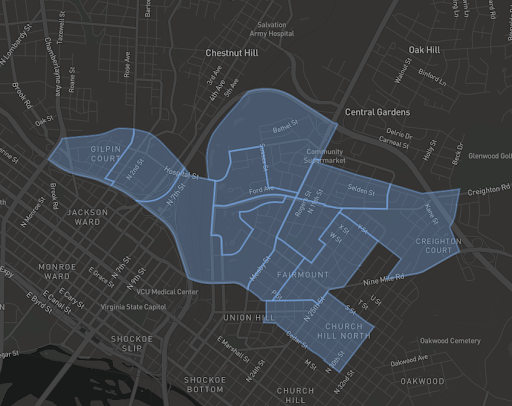

To understand which communities in Richmond depend on public transit the most, we identified the Census block groups with the highest percentage of households without access to a vehicle.

Block groups are important for transportation planning since they are typically small enough to measure pedestrian access to transit. Most of our block groups that lack access to vehicles are located in East Richmond.

Figure 1: Richmond block groups with a high percentage of households without access to a vehicle (Source: U.S. Census American Community Survey).

Where, When, and Why Are These Communities Travelling?

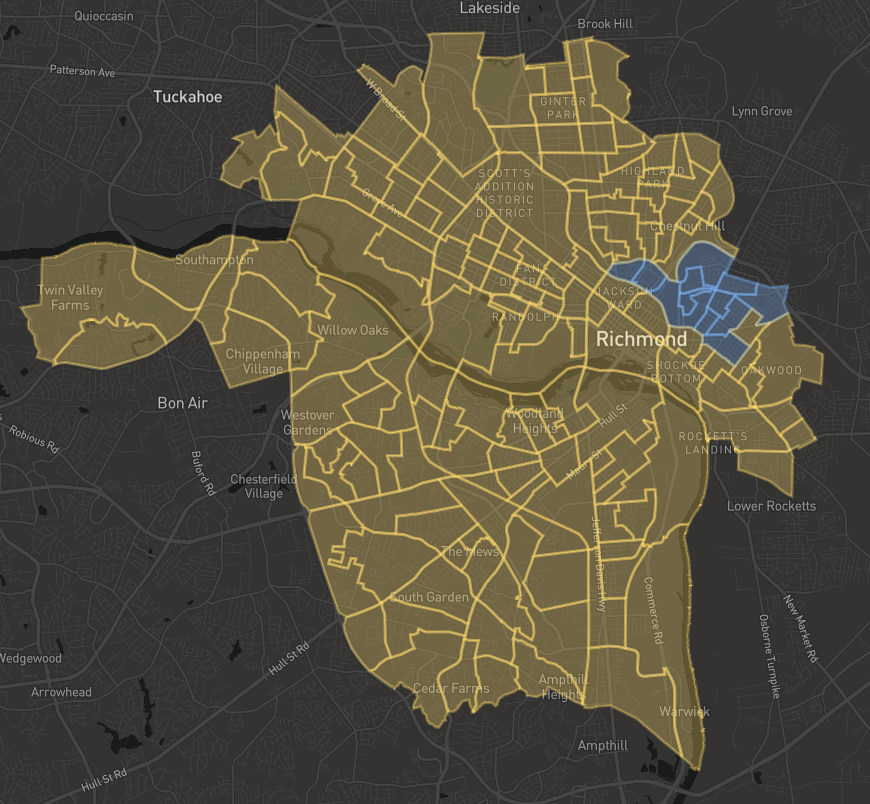

At StreetLight, we use Origin-Destination (O-D) analyses to study travel patterns between origins and destinations for vehicles, trucks, bikes, and pedestrians. For this study, we used an O-D analysis to identify:

- Most common destinations for each block group

- Time of day distribution of trips

- Difference between weekend and weekday travel patterns

Figure 2: Citywide Origin-Destination analysis for block groups with highest percentage of residents without access to a vehicle. Origin zones are in blue and destination zones are in yellow.

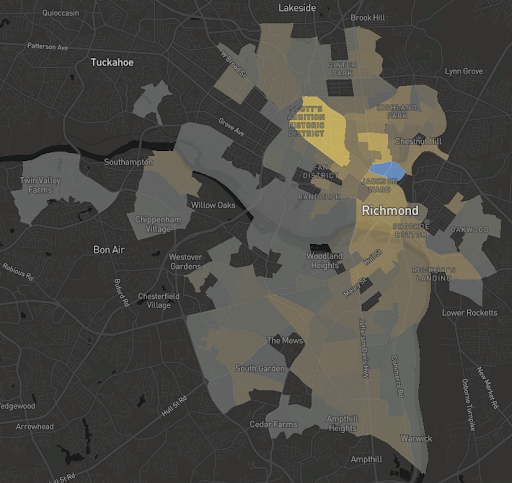

The O-D analysis helped us visualize Richmond’s travel patterns on a neighborhood scale. One neighborhood in particular emerged — Gilpin Court is one of the top block groups without vehicle access, and is also relatively isolated due to bisecting and surrounding highways. This area was recently profiled in the New York Times as an historically redlined neighborhood.

We analyzed typical weekdays in April and May 2020 to understand the top destinations for trips starting in this neighborhood. The top destination for the Gilpin Court neighborhood is a block group where two essential businesses are located: a grocery store and a hardware store (see Figure 3). There are also multiple corner markets located in Gilpin Court, but this is the closest full-service grocery store to the community.

Figure 3: The top destination for Gilpin Court (in blue) is a cluster of block groups (in yellow) with essential businesses including a grocery and hardware store.

While they may look close, the block groups are about 1.5 miles away (an estimated 30-minute walk or five-minute drive). The highways also limit mobility by making walking and biking difficult. This distance would be especially difficult if a person is carrying a week’s worth of groceries.

Current transit service through Gilpin Court runs north-south. Looking at the top destinations for trips originating in Gilpin Court we see that many of these trips are covered by the north-south service. There are multiple overlapping transit routes in this area that provide 15-minute frequency of transit service throughout most service hours. However, transferring to another route is required to reach these essential businesses. This not only increases travel time but also potential exposure to COVID-19.

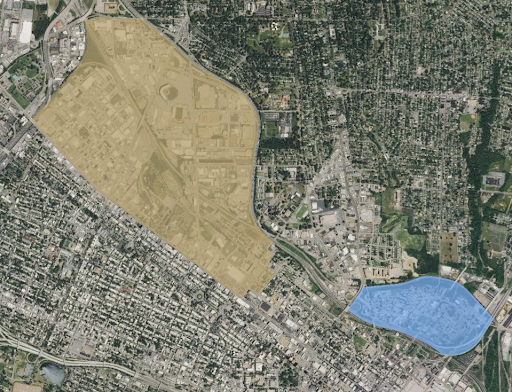

The bisecting highway is clearly visible in this aerial view of Gilpin Court (in blue) and the block groups (yellow) containing essential business destinations.

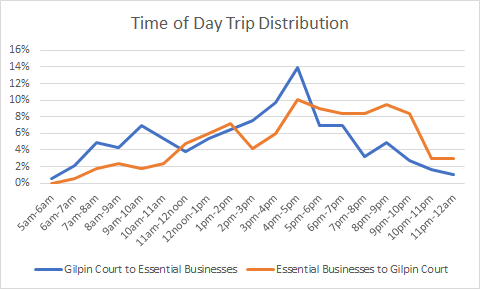

Analyzing the time-of-day transit distribution shows that the O-D pairs peak from midday to late evening, with fewer trips during the peak AM hours. Trips between Gilpin Court and essential businesses do not follow peak periods, with a higher number of trips occurring during the AM and PM peak.

Figure 5: Time-of-day trip distribution between Gilpin Court and essential businesses shows significant travel during off-peak periods.

How Can Transit Planning Support Essential Workers?

Measuring a neighborhood’s top trip destinations and time-of-day travel distribution is a powerful tool for transportation planners. It is especially useful for transit planning in low-income communities, where residents may not have access to vehicles, and instead rely on transit for essential travel.

In the case of the Gilpin Court neighborhood, planners could consider adding limited east-west transit services during the most in-demand hours between Gilpin Court and essential businesses. Connecting the residents of Gilpin Court to east-west transit routes via improved bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure could also be considered.

As low-income essential workers continue to carry a heavy societal burden during the pandemic, and are critical to re-establishing a healthy economy, we must prioritize their needs in transportation planning. As transit agencies re-establish service during the pandemic recovery period, Big Data can help them optimize services around these communities’ needs at a level of detail and speed that was previously unavailable.

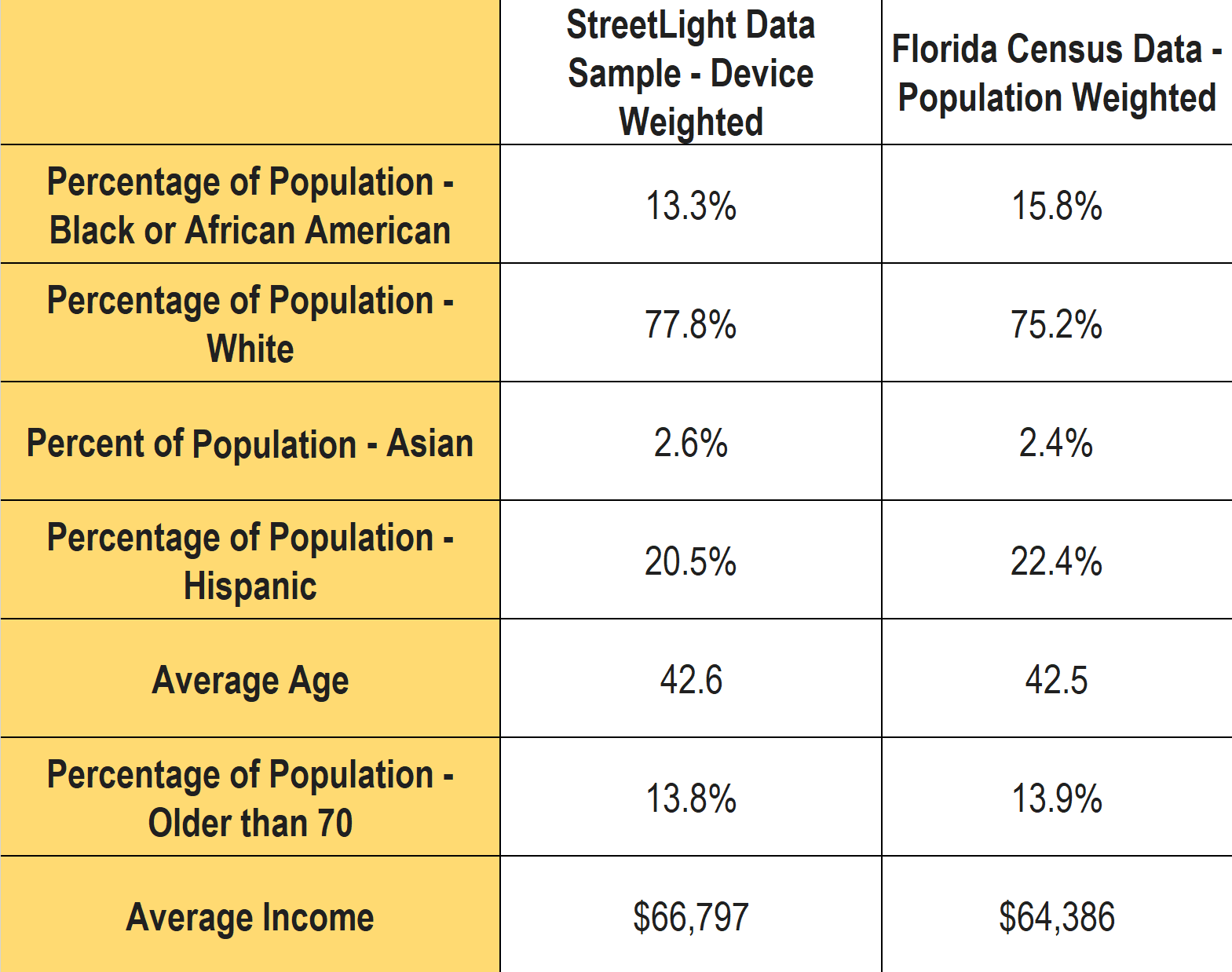

What we see in our data is that our sample for Florida closely represents the population at large. Another promising proof point that our data reflects the diverse characteristics of the geographies that our customers analyze with StreetLight. Lastly, it bears repeating that any metric that is expressed as StreetLight Volume has been normalized for any local bias or sampling variation.

Going Further: An Invitation to Explore Our Data

We’ve provided the “bird’s eye” view of our sample’s representativeness in Florida, and we also want researchers and analysts to understand how that plays out when the data is converted into StreetLight Metrics.

For more detail about the methodology and validation supporting our analyses, we invite you to explore our various white papers, and in particular Our Methodology and Data Sources.

1Note – the current StreetLight Indices for bikes, pedestrians, and trucks do not use the Census penetration for normalization, both use other grounding data instead. See the full documentation for details.